Chapter 1: The Hero of the Battle of Badon. 5

Chapter 2: Objections to Arthur. 11

Chapter 3: Historical Context. 20

………….The End of Roman Britain. 20

………….Pictish and Irish Raiders. 30

………….The Arrival of the Anglo-Saxons. 34

………….The Anglo-Saxon Conquest 38

………….The British Resistance. 46

………….The Warrior. 52

………….The King. 57

………….The Christian. 59

………….Arthur’s Retinue. 82

………….“The Old North”. 88

Chapter 5: The Battles of Arthur. 97

………….The First Battle: The Mouth of the River Glein. 97

………….The Second through Fifth Battles: On The River Dubglas in the Region Linnuis. 101

………….The Sixth Battle: On the River Bassas. 106

………….The Seventh Battle: In the Caledonian Forest 108

………….The Eighth Battle: The Fort of Guinnion. 112

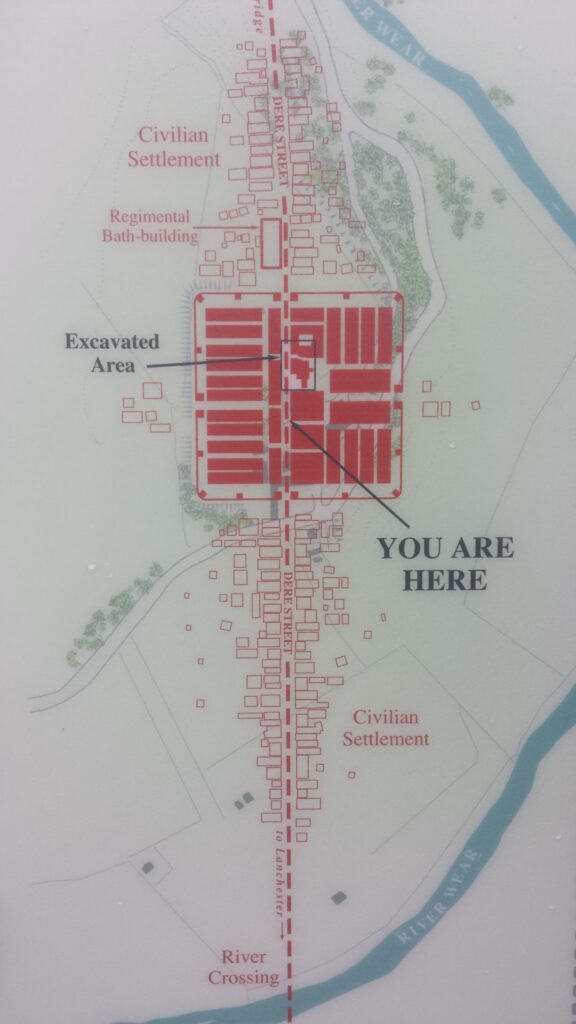

…………..The Ninth Battle: In the City of the Legion. 114

………….The Tenth Battle: On the bank of the River Tribruit 122

………….The Eleventh Battle: On the hill Agned. 125

………….The Twelfth Battle: On Mount Badon. 130

Chapter 6: Arthurian Legends. 143

………….Excalibur and the Sword in the Stone. 143

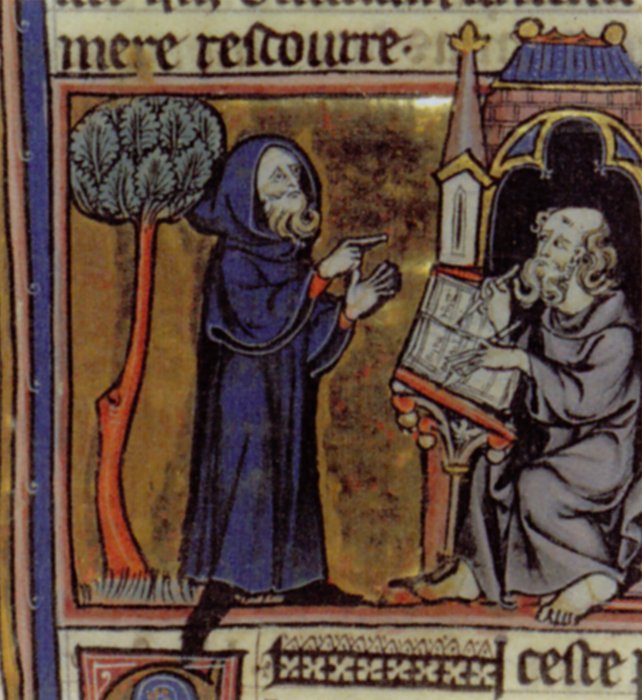

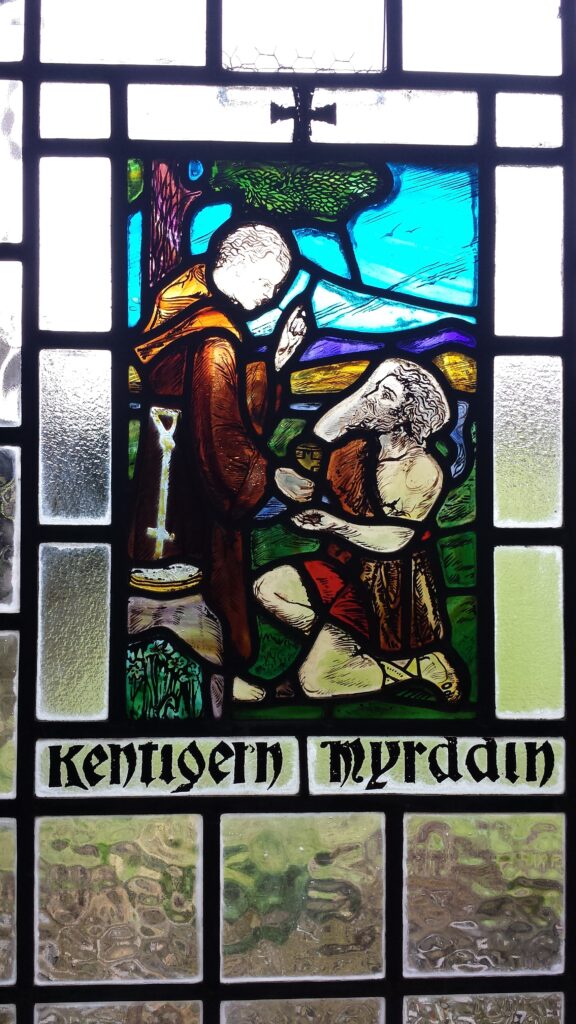

………….Merlin. 149

………….The Grail Legend and Joseph of Arimathea. 155

………….The Round Table. 161

………….Guinevere: Stories of Abduction and Betrayal 168

………….Mordred: Friend or Foe?. 172

………….Camlann: The Final Battle. 179

………….The Legend of Arthur. 186

Introduction

During the summer of 2006 while reading a couple of medieval books about King Arthur, I began to wonder where the Arthurian stories originated. As this question continued to build momentum in my mind, I decided to research the topic to satiate my own curiosity. At my university library I found books about the historical basis of King Arthur that pointed me to other primary medieval sources. I pored over each of them and took notes about everything of interest I could find on this topic. Before long, what started as a few brief notes became many pages of notes. What was most striking to me was how much the earlier sources differed from the later Arthurian romances. The adaptations I was familiar with were clearly based on the later romances. But I realized I had never encountered any adaptation of the story of King Arthur that was consistent with the earliest references to him as a Christian hero and patriot who led the defense of his people against invaders. As I delved deeper, I came to understand that many of the later stories about Arthur incorporated foreign elements from other cultures, regions, and time periods. In my conversations with friends and acquaintances on this topic, I didn’t encounter anyone else who had heard about these earliest portrayals of Arthur as a great battle commander defending his people, just as I hadn’t before I delved into the subject.

The more I researched the topic the more interesting insights I had, and after compiling many pages of my findings over the course of months and years, I accumulated a considerable amount of content. Many writings from other researchers have been especially helpful in my study of this topic. I have included their most relevant observations in this text, with the appropriate citations. While some writings satisfy me in regard to particular facets of the Arthurian stories, I have not felt fully satisfied with the entirety of each’s conjectures about the origins of the stories of King Arthur. For that reason, I have undertaken this work to attempt to combine what I believe are the most probable explanations for each aspect of the Arthurian stories, including my own thoughts and insights, along with accompanying evidence. After putting much effort into this compilation, I wish to now share my research with others who may also have interest in this topic.

I’m not an academic, nor am I professional writer. I’m an amateur historian and independent researcher. My intent is to educate and inspire readers about the origins and significance of the earliest Arthurian references, and in doing so to contribute to a deeper appreciation of the culture and history of the early medieval inhabitants of the British Isles. The earliest story of Arthur is a fragmentary story of freedom and of faith that is sure to inspire and edify. Whether someone thinks Arthur may have existed or not, or whether someone agrees with my insights or not, this book is certain to better inform the reader on various aspects of the legend that they may not have considered before. My hope is that the reader will find something of interest in my compilation, and to find inspiration in the earliest story of Arthur, the renowned battle commander and greatest hero of the early medieval Britons.

Chapter 1: The Hero of the Battle of Badon

The grizzled warrior surveyed the terrible scene by the last light of day. Some of his brave warriors had perished in the conflict, but many more of the enemy had fallen. Their bodies lay strewn about from the base of the hill to the ramparts of the fortification at the top. Wooden spears, shields, axes, and helmets, and the occasional sword or chain mail littered the battlefield. The cries of the wounded Britons sounded in the air as villagers came to their aid. Others flocked to the battlefield to scavenge the spoils of war from the bodies of the dead.

The siege had been wearisome, requiring the utmost vigilance against the enemy over the course of three days and nights. The British defenders tenaciously held the hill fort, and ultimately the courage and faith of the Britons prevailed over their enemies. The charge down the hillside led by this valiant battle commander drove the besiegers back. After suffering heavy losses, the Germanic warriors abandoned their designs and fled. Nearly a thousand of the enemy had fallen. They would not return to these lands anytime soon. The memory of their ignominious defeat would linger for at least a generation before they would again consider attempting to subjugate the native people of these lands.

The marauding army had sought dominion over the people of these lands, but his people had only sought to defend their families, their freedom, and the cause of their faith. But who was this hero of the Britons, who led such a crushing blow to the invaders? The only source that names the commander of the Britons at the battle on Mount Badon calls him Arthur.

****************************************************************************************************

The stories of King Arthur originated among the native Celtic people of early medieval Britain, the Britons. The fame of this hero spread throughout all the lands inhabited by the then unconquered Britons: Wales, Cornwall, Brittany, and “the Old North,” the region covering what is now the southern Lowlands of Scotland and the northernmost regions of England. As time went on, some of the descendants of these people who remained unconquered from the Anglo-Saxon invasion of Britain – primarily the Welsh – perpetuated and expanded the Arthurian stories of their forebears.

After the Norman conquest of England in the 11th century, they invaded Wales and gradually advanced for the next two centuries. During this time, the influence of Arthurian literature quickly spread to other regions as the Normans heard the Welsh and Breton stories and then disseminated them throughout England and to the continent beyond the borders of Brittany. This newly invigorated fascination led to the adoption of Arthurian themes by other western European cultures, who also introduced new foreign elements into the stories. By the 12th century, the stories of Arthur had become widespread throughout continental Europe.

After the complete conquest of Wales by king Edward I of England, the Welsh hero Arthur came to be adopted as a symbol of the English people, who projected elements of their own times, culture, and geography to the earlier legends preserved by the Welsh. Late medieval romances introduced contemporary imagery: Norman castles, dueling knights clad in plate armor, and jousting tournaments to win the favor of fair damsels – none of which previously existed in Arthurian lore. These later romances largely overshadowed – and supplanted – the earliest stories of the heroic Celtic battle commander who valiantly defended his people from the onslaught of foreign marauders. The romance L’Morte D’arthur, or “The Death of Arthur,” by the 15th century English writer Sir Thomas Malory came to be viewed as the definitive story of Arthur upon which most subsequent versions of the story are based.

Arthurian themes continue to permeate our culture down to the present day. The Sword in the Stone, the Knights of the Round Table, the Quest for the Holy Grail, the utopian society of Camelot, and others continue to find their way into literature, music, and film as elements of an elaborate Celtic myth. The stories of King Arthur have served as a source of inspiration for many renowned writers, including the likes of Dante Alighieri; Alfred, Lord Tennyson; Mark Twain; J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, and their fellow Inklings; John Steinbeck; and the stories even influenced composers Henry Purcell and Richard Wagner.

For many people in contemporary society, the legend of King Arthur has been relegated to myth, a mere icon of the fantasy genre of fiction. Yet even at the foundation of every myth are elements from the real world; a closer look at the origins of this legend suggests a much more inspiring story than the later romances present. Scholars continue to debate the historical basis of Arthur, but the question remains – Who was this battle commander that is mentioned in the “History of the Britons?” Was he the victor of the battle of Mount Badon? And why have stories about him endured and been revived throughout the generations for a millennium and a half?

Few insular British writings survive from the centuries following the Roman withdrawal from Britain. This may be rightly considered a dark age in Britain, in the sense that little is known of this time from contemporary sources. The only known surviving writings from this time period come from the British missionary to Ireland, Saint Patrick, and from the British monk, Gildas. The general lack of insular writings from this age of Britain, and the few surviving fragments, are insufficient to definitively confirm the existence of a historical British battle commander named Arthur. As noted by the 20th century Celtic linguist Kenneth Hurlstone Jackson:

Did King Arthur ever really exist? The only honest answer is, ‘We do not know, but he may well have existed.’ The nature of the evidence is such that proof is impossible.[1]

Later in the same essay, he notes:

Nothing is certain about the historical Arthur, not even his existence; however, there are certain possibilities, even probabilities.[2]

My intent is to explore these probabilities by examining the supporting evidence. In doing so, my focus is to attempt to discover the Arthur that is consistent with the earliest sources – a British patriot and battle commander, who, in the most desperate of times, stood firm in the defense of his people during the Anglo-Saxon invasion of Britain in the late 5th and early 6th centuries AD. The earliest generally acknowledged source to mention Arthur, the History of the Britons, describes him as a Christian battle commander who led his people in the defense of their homes and families, and that they overcame their enemies through their faith in Christ.

The 19th century Scottish historian William Forbes Skene compares the Arthur of the later medieval romances with how the earliest sources portray him:

That he bears here a very different character from the Arthur of romance is plain enough. That the latter was entirely a fictitious person is difficult to believe. There is always some substratum of truth on which the wildest legends are based, though it may be so disguised and perverted as hardly to be recognized; and I do not hesitate to receive the Arthur of [The History of the Britons] as the historic Arthur, the events recorded of him being not only consistent with the history of the period, but connected with localities which can be identified, and with most of which his name is still associated.[3]

And as the British historian Sheppard Frere, in his “Britannia: A History of Roman Britain,” notes:

The evidence is sufficient to allow belief that he had a real existence and that he was probably the victor of Mount Badon.[4]

An examination of the earliest sources about Arthur, as well as contextual evidence, seems to point to battles in northern Britain – in what is now southern Scotland and northern England. According to the first widely accepted source to mention Arthur, the History of the Britons, the rulers of the kingdom of Gwynedd in northern Wales claimed descent from Cunedda, a ruler of the Britons who came from the region around what is now Edinburgh and settled in northern Wales to drive out Irish colonists. Although the northeastern Britons were ultimately conquered by the Anglo-Saxons, the Welsh kingdoms remained independent for some time after, and in these places the stories of Arthur were preserved. The British Celticist Kenneth Hurlstone Jackson makes the interesting observation:

An important point in favour of a historical Arthur is the fact that we know of at least four, perhaps five, people called Arthur hailing from the Celtic areas of the British Isles who were born in the latter part of the sixth century and early in the seventh, whereas the name is unknown before (except for Arthur himself) and very rare later. Some national figure called Arthur must surely have existed at this time or a generation or two before, after whom they were all named, either directly or because their fathers or grandfathers had been. It is specially significant that Aedan mac Gabrain, king of Scottish Dal Riada, who had British connexions, christened one of his sons Arthur about 570 (and perhaps a grandson), since he headed what was meant to be a massive attempt to drive the English out of Northumbria.[5]

The 12th century Norman poet Wace also describes the liberties taken regarding this legend:

I know not if you have heard tell of the marvelous gestes and errant deeds so often of King Arthur. They have been noised about this mighty realm for so great a space that the truth has turned to fable and an idle song. Such rhymes are neither sheer bare lies, nor gospel truths. They should not be considered an idiot’s tale, or given by inspiration. The minstrel has sung his ballad, the storyteller told over his story so frequently, little by little he has decked and painted, till by reason of his embellishment the truth stands hid in the trappings of a tale. Thus to make a delectable tune to your ear, history goes masking as fable.[6]

The man regarded as the greatest English historian of the 12th century, William of Malmesbury, states:

This is that Arthur who is raved about even today in the trifles of the Britons —a man who is surely worthy of being described in true histories rather than dreamed about in fallacious myths—for he truly sustained his sinking homeland for a long time and aroused the drooping spirits of his fellow citizens to battle.[7]

In this book, I have gathered fragments of information from numerous historical and literary sources to attempt to piece together a picture of the Arthur described in the earliest sources, and to try to discover why his memory has been immortalized. Where possible, I have gone to the earliest manuscripts to obtain information, and if there is any confusion in the existing translations of these sources, I have gone back to the specific passages of text in question from the original Latin and Welsh languages for clarification. This work is not intended to be a comprehensive study of Arthurian literature, or a comprehensive study of the history of post Roman Britain, but the reader may find some additional insights through the study of those subjects. My hope for this search for Arthur is to inspire the reader with the stories of a man who led his people to defend their families and the cause of their faith, and also to educate the reader about some aspects of the peoples, cultures, and places of the late 5th and early 6th centuries.

Chapter 2: Objections to Arthur

The case against Arthur as a historical figure largely hinges upon the absence of direct references to him in three sources:

A more detailed investigation suggests that each of these omissions is wholly justifiable and reasonable when viewed in context.

On the Ruin of Britain

This 6th century text was written by a British monk named Gildas, who bemoans the moral decadence of his people and chastises several British kings for their immorality. According to the 9th century “History of the Britons” (of unknown authorship), Arthur led the Britons against the Anglo-Saxons at the Battle of Mount Badon. Gildas states he was born the same year as the Battle of Badon, making him a contemporary of Arthur. Although Gildas mentions the battle in his writings, he makes no mention of Arthur. This omission may be construed as evidence against the existence of a historical Arthur. However, a closer look at the purpose for which Gildas wrote his text shows a clearer perspective. Gildas himself states,

It is my present purpose to relate the deeds of an indolent and slothful race, rather than the exploits of those who have been valiant in the field.

True to his stated purpose, Gildas only mentions one British war hero, but seven British tyrants in the period of time immediately preceding and during the Anglo-Saxon invasion.[8] Although he does not name Arthur, he also does not specify who led the Britons at the Battle of Mount Badon. Another individual notably absent from Gildas’ writings is Germanus of Auxerre, the historically recognized 4th-5th century Roman Catholic Bishop from France who allegedly assisted the Britons to win an early victory against Saxon raiders without force of arms. Rather than take this as evidence against the existence of Germanus, this should also be taken in context of Gildas’ previously stated purpose. Leslie Alcock in his book “Arthur’s Britain” astutely notes:

It may seem strange that Gildas should not name the victor of Badon, and this line of argument would incline us to infer that Ambrosius is the subject of all this military activity. But two further points arise. First, Gildas is altogether sparing of names of persons and places. In the whole of Section B, apart from biblical passages and classical writers whom he wishes to quote, he names only two Roman emperors, Tiberius and Diocletian; three British martyrs, Alban, Julian and Aaaron, the usurper Magnus Maximus; Aeitus the commander-in-chief in Gaul; and Ambrosius. Even in the critical incident of the invitation to the Saxons he names neither the superbus tyrannus nor the Saxon leaders. We may therefore be gratefully surprised that he should name Ambrosius and Badon at all. Secondly, bearing in mind that his purpose is homily and not history, we need not expect names, and the name of the general might fit oddly with that of the battle in what is, in the main, a sermon. It has been said, ‘what English bishop, castigating the vices of his compatriots about 1860, would be so clumsy as to allude to “the battle of Waterloo, which was won by the Duke of Wellington”?’[9]

An additional explanation comes from the 12th century text The Life of Saint Gildas by Caradoc of Llancarfan. In this manuscript, he claims that Gildas’ older brother Hueil rebelled against Arthur by raiding settlements and pillaging them until he was killed by Arthur on the Isle of Man. This could explain why Gildas does not mention Arthur in his text, but the validity of this source is uncertain.

The Ecclesiastical History of the English People

This 8th century text was written by the English monk Bede, a Roman Catholic. Bede recounts the defeat of the Anglo-Saxons at the Battle of Badon Hill in his “Ecclesiastical History of the English People,” but he does not mention Arthur – who other sources claim as the commander of the British forces in that battle. However, he also does not name who the battle commander of the Britons was at this battle. The reasons for Bede’s omission are unknown, although he clearly uses Gildas’ writings as the source material for his own writings on this time period. Thus, he may have omitted the name of Arthur simply because Gildas did not include it in his text.

The Britons for the most part have a national hatred for the English, and uphold their own bad customs against the true Easter of the Catholic Church; however, they are opposed by the power of God and man alike, and are powerless to obtain what they want. For, although in part they are independent, they have been brought in part under subjection to the English.[10]

Perhaps some of the Arthurian traditions were intertwined with Pelagianism or Celtic Christian beliefs, and which would therefore be excluded by Bede, although this remains only conjecture.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

This 9th century history was compiled during the reign of King Alfred the Great. The “Anglo-Saxon Chronicle,” a collection of manuscripts documenting a timeline of significant events from the Anglo-Saxon perspective, mentions neither Arthur nor the Battle of Badon Hill. This may be taken as evidence against a historical Arthur. However, it must be noted that the entries in the Chronicle only record the victories of the Anglo-Saxons and the losses of the Britons. Since Arthur was a Briton who was renowned for defeating the Anglo-Saxons multiple times in battle, we can reasonably expect an absence of an account of his victories in the early Anglo-Saxon histories.

Furthermore, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is not concerned with events north of the Humber River but only records events south of it, whereas the 9th century text Historia Britonum, or, “History of the Britons” (one of the earliest sources to name Arthur), indicates a northern locale for Arthur’s battles, as suggested by the 19th century Scottish historian W. F. Skene.

That the events here recorded of him are not mentioned in the Saxon Chronicle and other Saxon authorities, is capable of explanation. These authorities record the struggle between the Britons and the Saxons south of the Humber [River]; but there were settlements of Saxons in the north even at that early period, and it is with these settlements that the war narrated in the ‘Historia Britonum’ apparently took place.[11]

Probable locations for the sites of Arthur’s battles listed in the “History of the Britons” will be presented later in this work.

Composite Figures

Theories abound that the legendary Arthur may be based on or a composite of several historically recognized figures or an extrapolation of one of them. Some of these historical figures considered as forming the basis for King Arthur include:

-

- Lucius Artorius Castus, a Roman military commander over the Roman Legion garrisoned at the city of York in Britain during the 2nd – 3rd century AD, as proposed by Kemp Malone.

-

- Ambrosius Aurelianus, a Romano-Briton nobleman who instigated the British resistance against the Anglo-Saxon invasion in the 5th century AD.[12]

-

- Riothamus, a Romano-Briton military commander in Gaul[13] who was defeated in battle against the Visigoths in the late 5th century AD, as proposed by historian Geoffrey Ashe.

-

- Arthuis[16], son of Masgwid, a British ruler of the kingdom of Elmet in the 6th century AD.

-

- Arthur[17], son of Petr, a Welsh ruler of the kingdom of Dyfed during the late 6th – early 7th century AD.

-

- Athrwys son of Meurig, a Welsh prince of the kingdom of Gwent in the 7th century AD.

The suggestion that one of these figures, or a composite of multiple figures, may have inspired the legend of Arthur presents more problems than it resolves. Most of the candidates are from different time periods – either too early or too late – for the Arthur presented in the “History of the Britons.” Of the possible contemporaries of Arthur, Riothamus was active on the continent with no known activity in Britain, while attempts to conflate Ambrosius Aurelianus with Arthur assume that because Gildas mentions Ambrosius in the sentences prior to mentioning the battle of Badon, that Ambrosius was the British commander of that battle. However, Gildas does not explicitly state who commanded the Britons at Badon hill. He writes:

After this, sometimes our countrymen, sometimes the enemy, won the field, to the end that our Lord might in this land try after his accustomed manner these his Israelites, whether they loved him or not, until the year of the siege of Mount Badon, when took place also the last almost, though not the least slaughter of our cruel foes, which was (as I am sure) forty-four years and one month after the landing of the Saxons, and also the time of my own nativity.

The early Welsh traditions portray Arthur as the son of Uther Pendragon, and as a British war commander who battled Anglo-Saxon invaders in the late 5th to early 6th century AD.

The Sources

While examining the sources that reference the battle commander Arthur, it is important to note that many records may not have survived from the 5th or 6th Centuries AD due to wear, decay, the ravages of war, and other factors. This period in the history of Britain is a relative “dark age” due to the limited surviving sources from this time. The 6th century British monk Gildas states:

I shall not follow the writings and records of my own country, which (if there ever were any of them) have been consumed in the fires of the enemy, or have accompanied my exiled countrymen into distant lands, but be guided by the relations of foreign writers, which, being broken and interrupted in many places, are therefore by no means clear.

Researchers who applied a statistical model for unseen species to medieval manuscripts estimate that up to about 68% of medieval works have survived, with only up to about 9% of physical manuscripts surviving to the present.[18] From the early medieval time period in Britain it is not uncommon to find information that comes from only one source and can’t be found directly anywhere else. The fact that some manuscripts survived while others didn’t in no way invalidates surviving information that comes from a single source. That being said, it is important to explore additional evidence to support or dispute that information.

As noted by F. F. Bruce, the fact that the surviving manuscripts about Arthur come from later centuries, does not detract from the possibility or probability of Arthur’s existence:

The History of Thucydides (c. 460-400 BC) is known to us from eight (manuscripts), the earliest belonging to circa A.D. 900, and a few papyrus scraps, belonging to about the beginning of the Christian era. The same is true of the History of Herodotus (c. 488-428 BC). Yet no classical scholar would listen to an argument that the authenticity of Herodotus or Thucydides is in doubt because the earliest (manuscripts) of their works which are of any use to us are over 1,300 years later than the originals.[19]

Fragments of information from earlier manuscripts, which have perished, certainly have been incorporated into later compilations, and in some cases, have been embellished. The 12th century Norman cleric Geoffrey of Monmouth claims that he translated “a very old book in the British tongue,” into Latin, “which set out in excellent style a continuous narrative of all their deeds…”, forming the basis for his “History of the Kings of Britain.” Geoffrey probably did indeed base some of his work on an earlier source and there is no reason to suppose this was a mere fabricated literary device. However, his writings are not reliable due to the introduction of many fantastical elements into the story, such as the portrayal of Arthur as conqueror of northwestern Europe and would-be conqueror of Rome. Thus, it is challenging, if not impossible in many instances, to differentiate between Geoffrey’s source material and what may be his own embellishments to it. But to indiscriminately reject every detail of Geoffrey’s work is unfounded since there are certainly elements of truth embedded within his fictional narrative.

Another source, the 13th century Welsh manuscript the “Book of Aneirin,” contains a reference to Arthur in the epic poem “The Gododdin”, which was most likely from a poem actually written by the British bard Aneirin in the 7th century. If correct, this would be the earliest Arthurian source.

Some may suggest that references to Arthur in early sources may have been interpolated by later scribes to fabricate a false historical basis for him, but the evidence for this theory is lacking. Thus, rather than utterly discarding some sources because they don’t mesh with a particular narrative, it is reasonable to expect that there may be fragments of truth from earlier sources imbedded even within some embellished tales. The presence of mythological material in some sources neither negates nor discredits the truthfulness of earlier source material. Although the sources merely provide limited fragments of information about Arthur, we can piece together an understanding, albeit limited, of who he was and why he became legend. As would be expected, the primary sources about Arthur mainly come from early Welsh writers.

Chapter 3: Historical Context

The End of Roman Britain

After centuries of occupation, the Romans were gone. From the reconnaissance campaign of Julius Caesar in 55 BC to the full-scale invasion of the Roman Emperor Claudius in AD 43 down to the final withdrawal of the Roman soldiers around AD 410, the Roman Empire had left its imprint on the island of Britain. The Romans developed an unprecedented infrastructure in Britain by building towns and constructing a vast network of roads to better facilitate transportation. Additionally, they introduced some of the comforts of Rome to the people of Britain, including luxurious baths, stately villas, and exotic imported goods. The increased urbanization and the integration of the Latin language and culture into the native British tribes led to the development of a Romano-British culture.

To defend their provinces in Britain, they established forts at key locations and constructed two walls in the north – Hadrian’s Wall and the Antonine Wall – to protect against incursions of the Caledonian tribes. With three legions garrisoned in Britain, the Roman military presence there was more considerable than in most provinces. While some studies suggest that the Romans did not leave much of an imprint on the genetics of Britain, they certainly left one on the landscapes and the culture.

The Roman conquest of Britain began in the southeast and gradually spread to the west and then to the north. Although the Roman soldiers were not nearly as numerous as the Britons, their superior discipline and military tactics proved highly effective against the less organized and less well-equipped Britons. Additionally, the Romans exploited existing rivalries between neighboring British tribes to conquer them one tribe at a time.[20]

As Roman control increased, the province of Britannia was established by the Senate and governors were appointed to maintain order, exert Roman influence, and expand the dominion of the Roman Empire. But the entirety of the island never fell under Roman rule and governance of the province of Britain proved to be unstable. Some refused to submit to Roman rule. Rebellion among conquered tribes, incursions of foreign raiders, and usurpation by Roman governors defined the Roman occupation of Britain. The betrayal and brutality of the Romans toward their allies, the British Iceni tribe, during the reign of the Emperor Nero led to the revolt of Queen Boudicca and her people in southeastern Britain from 61-60 AD. But this revolt was quickly crushed and Roman order was once again established.[21]

Within a couple of decades, the Roman Emperor Vespasian appointed the nobleman Gnaeus Julius Agricola governor of Britain. Upon arriving in Britain, Agricola immediately attacked and subjugated the British Ordovices tribe in Wales and conquered the island of Angsley (modern day Mona). He pressed northward, conquering what is now northern England and southern Scotland, and established forts across the line from the Clyde River to the Firth of Forth line.[22] Agricola continued northward, leading a military campaign against the Caledonians of northern Britain by land and sea. In 84 AD he defeated the Caledonians led by Calgacus at the Battle of Mons Graupius but withdrew the campaign for the winter. Shortly thereafter, Emperor Domitian recalled Agricola to Rome to celebrate his triumph over the Britons and Caledonians, and the Roman soldiers withdrew to the forts along the Firth-Clyde line.[23] The Caledonian tribes retaliated by destroying several Roman forts around 105 AD, and the Romans retreated to defenses retreated south of the line from the Solway Firth to the Tyne River.

In 117 AD, the Emperor Hadrian appointed the general Quintus Pompeius Falco as the governor of Britain. Upon arriving in Britain, the governor quelled an uprising in the north. While touring the Roman provinces, Emperor Hadrian visited Britain in 120 AD. While there, he ordered the construction of a wall spanning the width of Britain from the Solway Forth to the River Tyne in northern Britain, a distance of 73 miles (75 Roman miles) to “separate the Romans from the barbarians.”[24] A newly appointed Roman governor oversaw construction of the wall. East of River Irthing, the wall was made of squared stone, 9.8 feet wide and 16-20 feet high; west of the river the wall was made of turf, 20 feet wide and 11 feet high. The wall was completed ca. AD 128.

Hadrian’s successor, Emperor Antoninus Pius (138-161), advanced Roman rule 100 miles north of Hadrian’s Wall, where he commissioned the construction of a second northern wall spanning from the Firth of Forth to the River Clyde, a distance of 38 miles (40 Roman miles). The new Antonine Wall was completed in 142 AD. This expansion proved to be short-lived when the Brigantes, a northern British tribe, revolted and drove the Romans south again to Hadrian’s Wall. Between 155-157 AD. A Roman Governor suppressed the uprising and recaptured the Antonine Wall, only to abandon it again by 163 or 164 AD. The main force of the Romans retreated back to Hadrian’s Wall, but a few small Roman outposts beyond the wall continued to be held by the Romans until at least 180 AD, including Newstead and 7 other small outposts. The Roman dominion there lasted no more than 20 years in most areas, but in some parts it lasted nearly 40 years.

In 175 AD, a company of 5,500 cavalry levied in the province of Sarmatia arrived in Britain. In what was referred to in antiquity as the “greatest struggle” of Emperor Commodus’ reign, Hadrian’s Wall was breached by the northern British tribes, who overran the forts and killed the Governor of Britain in 180 AD. In 184 AD, a Roman general drove them back to the north of Hadrian’s wall.[25] By 187, the Roman garrison in Britain rebelled, and a new governor, Publius Helvius Pertinax Augustus, was appointed to quell the uprising, only to be resign his commission after being attacked by the soldiers there.[26] After the death of Emperor Commodus, Pertinax briefly became Emperor (AD 193) until he was murdered, after which Emperor Septimius Severus (193-211) ascended to the throne.

Three Roman legions were stationed in Britain to quell uprisings among the conquered Britons and to defend against the incursions of the Britons and Picts beyond Roman jurisdiction to the north. The legions were stationed in York (Eboracum), Chester (Deva), and Caerleon (Isca Silurum). With 3 legions under their command, the Governors of Britain were disproportionately powerfully provincial governors in the Roman Empire, posing a potential threat to the Emperor’s rule.

The temptation became too great, and the governor of Britain, Clodius Albinus, usurped the title “Emperor” and crossed over into Gaul with the legions of Britain. Emperor Severus battled against Albinus in Gaul in 195, and ultimately defeated him in 196. Desperate for peace, the next Roman Governor of Britain paid tribute to one of the British tribes to appease them during his rule, beginning in 197 AD.[27] Recognizing the need to reduce the power of the Roman governor of Britain, Severus divided the province into two provinces in 197 AD: Britannia Superior and Britannia Inferior, ushering in the period referred to as “The Long Peace.”

The next governor, Lucius Alfenus Senecio (AD 205-207), appealed to Emperor Severus in 207 for military aid against the northern tribes, who were “rebelling, over-running the land, taking loot and creating destruction.”[28] Upon learning of the conflict in Britain, the Emperor Severus personally led a military campaign north of Hadrian’s Wall against the Maetae and Caledonians with 20,000 soldiers in 208 or 209 AD. Guerilla raids amidst the unfamiliar terrain incurred heavy casualties on the Roman soldiers. Though the Caledonians and Romans didn’t meet in battle, the Caledonians sued for peace; Severus signed peace treaties with them, allowing Roman occupation of the central Lowlands. Later that year, the Caledonians and Maetae resumed the conflict against the Romans.[29] Emperor Severus prepared to launch another campaign against them to exterminate them, but fell ill and withdrew to Eboracum (York) where he died shortly thereafter.[30] The Roman frontier reverted back to Hadrian’s Wall.

In AD 260, the Roman general Postumus usurped the title “Emperor” and established a “Gallic Empire” comprising the Roman provinces of Gaul, Germania, Britannia, and Hispania to battle against Emperor Gallienus. However, Postumus was murdered by his own soldiers in AD 269. By 274, Emperor Aurelian reclaimed the rebellious provinces and reunited them with the Roman Empire. In 281 a tribune named Bonosus proclaimed himself “Emperor,” which was shortly thereafter quelled by Emperor Probus. By AD 285 the Roman Empire split into Western Roman Empire and the Eastern Roman Empire.

In AD 286, the fleet commander of the Britannic Sea, Carausius, proclaimed himself Emperor of Britain and northern Gaul. Emperor Maximian attempted to cross over to Britain to suppress the revolt, but failed when his fleet was destroyed by storms in 288. In AD 293 Emperor Constantius Chlorus became co-Emperor with Emperor Maximian and invaded Gaul.[31] Carausius was overthrown by one of his men, who was in turn defeated by Emperor Constantius in 296.[32] Constantius set things in orders and divided the two Provinces of Upper Britannia and Lower Britannia into four Provinces to attempt to reduce the power of the governors even more:

-

- Maxima Caesarensis (from Upper Britannia)

-

- Britannia Prima (from Upper Britannia)

-

- Flavia Caesariensis (from Lower Britannia)

-

- Britannia Secunda (from Lower Britannia)

Constantius repaired Hadrian’s Wall and the associated forts. In the same year, Emperor Diocletioan made Britain a diocese of the prefecture of Galliae – along with Gaul, Germania, and Hispania – so a fifth governor was added to Britain.

Around this time, in the late 3rd century AD, Saxon raids by sea provoked the Romans to construct forts on the southern and eastern shores of Britain, becoming known as the “Saxon Shore” (litus Saxonicum).[33]

In 305 AD, Emperor Constantius and his son, Constantine began a military campaign beyond Hadrian’s Wall to subjugate the Picts – the people the Romans previously called the Caledonians.[34] After achieving some success, they withdrew to Eboracum (York) for the winter to plan the next stages of the campaign, but Emperor Constantius unexpectedly died. His son, Emperor Constantine I “the Great” was proclaimed Roman Emperor in York in 306 – the first legitimate emperor to be given that title while in Britain. His son Emperor Constans succeeded him, but was assassinated in 350.

In AD 368 the Roman garrison stationed at Hadrian’s Wall rebelled. At the same time, the Attacotti, Scotti, Picts, and Saxons coordinated an attack, conquering the northern and western regions of Britannia. Roving bands of soldiers and slaves raided the towns and countryside, wreaking havoc. The 4th century Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus noted that: “It will be sufficient here to mention that at the time the Picts, divided into two tribes called Dicalydones and Verturiones, and likewise the Attacotti, a very warlike people, and the Scots were all roving over different parts of the country and committing great ravages. While the Franks and the Saxons who are on the frontiers of the Gauls were ravaging their country wherever they could effect an entrance by sea or land, plundering and burning, and murdering all the prisoners they could take.” [35]

Emperor Valentinian I dispatched Theodosius with an army, who reconquered the cities granting amnesty to deserted soldiers, executing mutineers, and driving the invaders out of the provinces, thereby establishing peace. They retook Hadrian’s Wall and reestablished the garrisons in the forts. In AD 369 Count Theodosius established a fifth Roman Province, Valentia, in the far north.

Maximus

Incursions by the Scots and Picts ravaged the Roman lands to the north, and in AD 381, the Roman general Magnus Maximus drove them back beyond the Roman frontier. In AD 383 he was proclaimed Emperor of the Western Roman Empire by his soldiers. Crossing over to Gaul, he took with him much of the Roman infrastructure of Britain – soldiers, armed bands, governors, and youth – never to return and therebyexposed Britain to foreign incursions.[36] Leading the Roman soldiers from Britain to Gaul, he battled Emperor Gratian and defeated him, usurping rule of Britain and Gaul as Emperor Augustus. In the early Welsh stories, Maximus is acclaimed as the founder of British kingdoms and is referenced in numerous stories. Early Welsh poems and genealogies refer to him as “King Maximus” (Wledig Macsen/Maxen). [37] According to the “History of the Britons,” Maximus settled some of the British soldiers who came with him to Gaul in a place called Armorica, which later came to be known as “Britanny,” or “little Britain.” The British men married Gallic women, becoming the ancestors of the modern Bretons. Maximus’ ambitions got the best of him, and while invading Italy to secure control of the entire Western Roman Empire, he was defeated by Emperor Theodosius in 388. Following his defeat, the Roman Senate passed “Damnatio Memoriae” or “Damnation to the Memory” on Maximus to expunge him from the memory and writings of the people. While the Romans purged him from their memory, the Britons revered him as the founder of a royal dynasty. Inscriptions on the Pillar of Eliseg, a 9th century Welsh monument, mentions an ancestral line through Britu, the son of Sevira, daughter of Maximus. Gildas writes of Maximus:

At length also, new races of tyrants sprang up, in terrific numbers, and the island, still bearing its Roman name, but casting off her institutes and laws, sent forth among the Gauls that bitter scion of her own planting Maximus, with a great number of followers, and the ensigns of royalty, which he bore without decency and without lawful right, but in a tyrannical manner, and amid the disturbances of the seditious soldiery. He, by cunning arts rather than by valour, attaching to his rule, by perjury and falsehood, all the neighbouring towns and provinces, against the Roman state, extended one of his wings to Spain, the other to Italy, fixed the seat of his unholy government at Treves, and so furiously pushed his rebellion against his lawful emperors that he drove one of them out of Rome, and caused the other to terminate his most holy life. Trusting to these successful attempts, he not long after lost his accursed head before the walls of Aquileia, whereas he had before cut off the crowned heads of almost all the world.

The withdrawal of the Roman soldiers under Maximus marked the beginning of the end of Roman rule in Britain. The provinces of Britain continued under some degree of Roman control, albeit significantly weakened. During an invasion by the Picts in AD 398, the Roman general Flavius Stilicho sent aid to fortify the frontier at Hadrian’s Wall.[38] It may have also been during this time that the legendary Irish king Niall “of the Nine Hostages” raided the western and southern coasts of Britain and captured and enslaved some of the inhabitants.

Constantine III

In AD 407 the provinces in Britain rebelled, and the remnants of the Roman army chose a common soldier by the name of Constantine to lead them as their general. Constantine proclaimed himself Emperor Constantine III and mustered all the soldiers he could from Britain and crossed with them over the British Sea (Mare Brittonum) to Gaul.

Not long thereafter, the Britons threw off the Roman yoke and armed themselves to defend against the Anglo-Saxon invaders. According to the Byzantine historian Zosimus, Constantine was to blame for the expulsion of the Romans because he hadn’t taken strong enough measures against the Saxon raids.[39] The Britons and Gauls revolted, rejected Roman law, and took up arms.

The barbarians above the Rhine, assaulting without hindrance, reduced the inhabitants of Britain and some of the Celtic peoples to defecting from the Roman rule and living their own lives, independent from the Roman laws. The Britons therefore took up arms and, braving the danger on their own behalf, freed their cities from the barbarian threat. And all Armorica [Brittany] and the other Gallic provinces followed their example, freed themselves in the same way, expelling the Roman officials and setting up a constitution such as they pleased.[40]

Gerontius … winning over the troops there [in Spain] caused the barbarians in Gaul to rise against Constantine. Since Constantine did not hold out against these, the greater part of his strength being in Spain, the barbarians from beyond the Rhine overran everything at will and reduced the inhabitants of the British Island and some of the peoples in Gaul to the necessity of rebelling from the Roman empire… Now the defection of Britain and the Celtic peoples took place during Constantine’s tyranny, the barbarians having mounted their attacks owing to the carelessness in administration.[41]

In another text describing the 16th year of the reign of Honorius – AD 409 or 410, the Byzantine historian Zosimus writes:

The Britains were devastated by an incursion of the Saxons.[42]

In AD 410, the city of Rome was sacked by the Visigoths under Alaric I and the British Roman Emperor Constantine III was defeated by a general of Emperor Honorius. With Constantine’s defeat, the Roman standard no longer flew over Britain after over 300 years of Roman occupation. The Byzantine historian Procopius (ca. 500-570) writes:

From that time onwards it remained under [the rule] of tyrants.[43]

Pictish and Irish Raiders

After the departure of the Romans, the Britons reverted to their tribal allegiances and emerged as numerous independent British kingdoms. Alliances were formed between some of the British kingdoms to defend their people against the threats and internal strifes began between others. The Britons were not a wholly unified people; they were made up of tribes governed by regional kings. In Britain a process of de-urbanization began as people moved from the cities and villas to the hillforts and the surrounding countryside. The Britons stopped using coins, pottery, but still used metal, glass, and leather or wood vessels. The regions that had been occupied by the Romans retained much of the Romano-British culture.

The withdrawal of the Romans left the borders of Britain largely undefended. After centuries of occupation, the native Britons had grown accustomed to the protection of the Roman soldiers from foreign raids so that one almost contemporary writer states they were “utterly ignorant…of the art of war.”[44] Seizing this opportunity to prey upon their complacent neighbors, the Picts of northern Britain and the Scots of Ireland ventured beyond their borders and plundered the weak and ill-prepared Britons, enslaving many and taking the spoils of their raids back to their own lands. Gildas writes of the situation in Britain:

After this, Britain is left deprived of all her soldiery and armed bands, of her cruel governors, and of the flower of her youth, who went with Maximus, but never again returned; and utterly ignorant as she was of the art of war, groaned in amazement for many years under the cruelty of two foreign nations—the Scots from the north-west, and the Picts from the north.

It was in these tragic circumstances that a young man named Patricius was abducted from his home in Britain by Irish raiders and enslaved for the next several years in Ireland. These experiences became a major turning point in his life, leading him to believe in the Christian faith of his parents and grandparents, and devoting the remainder of his life to a Christian ministry among the pagan Irish, thereby gaining renown down to the present day, the celebrated Saint Patrick. He writes:[45]

I, Patrick, a sinner, the rudest and least of all the faithful, and most contemptible to very many, had for my father Calpornius, a deacon, the son of Potitus, a priest, who lived in Bannaven Taberniae, for he had a small country-house close by, where I was taken captive when I was nearly sixteen years of age. I knew not the true God, and I was brought captive to Ireland with many thousand men, as we deserved; for we had forsaken God, and had not kept His commandments, and were disobedient to our priests, who admonished us for our salvation. And the Lord brought down upon us the anger of His Spirit, and scattered us among many nations, even to the ends of the earth, where now my littleness may be seen amongst strangers. And there the Lord showed me my unbelief, that at length I might remember my iniquities, and strengthen my whole heart towards the Lord my God, who looked down upon my humiliation, and had pity upon my youth and ignorance, and kept me before I knew him, and before I had wisdom or could distinguish between good and evil, and strengthened and comforted me as a father would his son.

Colonists from Ireland secured footholds on the western coasts of the island (Dalriada and Ui Liathain); while Pictish warriors launched incursions from the north. Unable to or ignorant of how to defend themselves, the suffering Britons dispatched messengers to Rome, pleading for protection and promising submission to the rule of Roman law. Upon receiving the British ambassadors, Roman officials swiftly dispatched a legion to Britain to repel the foreign raiders. The Roman soldiers landed on the shores of Britain at a site occupied by Pictish or Irish raiders, and immediately a battle ensued in which large numbers of raiders were slain and the remainder were driven beyond the borders. Once the raiders had been driven back, the Romans advised the Britons to refortify the Antonine Wall.

Upon the departure of the Romans, the raiders returned. The Britons appealed to Rome for help once more, and again, the Roman soldiers came to Britain and drove the raiders back. This time they informed the Britons that they could not return again to assist due to troubles on the continent, and:

[T]hat the islanders, inuring themselves to warlike weapons, and bravely fighting, should valiantly protect their country, their property, wives and children, and, what is dearer than these, their liberty and lives…”

Seeing the extremity of the Britons, the Romans supervised the fortification of Hadrian’s Wall and taught the Britons how to make weapons. They fortified towers on the south coast, the “Saxon shore” and trained the Britons in the art of war, and then departed Britain. The Picts and Scots shortly thereafter attacked with greater force, and conquered all the northern lands up to the wall. They drove the Britons from their fortifications and pursued them and many were forced to flee without any provisions. In desperation, some of the Britons drafted a letter to the Roman General Flavius Aetius (391-454 AD), who was serving as a Consul – one of the two senior administrative magistrates of the Roman Empire. The letter reads:

To Aetius, now consul for the third time: the groans of the Britons.

The barbarians drive us to the sea; the sea throws us back on the barbarians: thus two modes of death await us, we are either slain or drowned.”[46]

Flavius Aetius served as the Consul or Rome for the third time between 446 and 454, dating the letter between those years. However, the Romans could not help, and many of the fleeing Britons surrendered to the raiders for provisions, while others hid in the wild and came out to battle against the invaders. Gildas writes:

And then it was, for the first time, that they overthrew their enemies, who had for so many years been living in their country; for their trust was not in man, but in God; according to the maxim of Philo, “We must have divine assistance, when that of man fails.”

This success drove the invaders back, but before long they returned. The Scots established a foothold at the northwestern extremity of Britain and returned to plunder, as well as the Picts. After a brief period of prosperity, they Britons received intelligence that the raiders were returning in greater force.

The Arrival of the Anglo-Saxons

Amidst the Irish pirates from the west and the Pictish raiders from the north, one of the powerful British kings by the name of Guorthigern (usually Latinized as Vortigern, although no letter “v” exists in the Old Welsh language),[47] met with a council and devised a plan to deal with these raiders and pirates. Since the Britons had lost the art of war during the Roman occupation, they determined that they would hire mercenaries from Germanic tribes on the continent who were skilled in warfare – including Angles from Anglia, Saxons from Saxony, and Jutes from Jutland – each of these tribes close kin of each other. The British monk Gildas writes:

For a council was called to settle what was best and most expedient to be done, in order to repel such frequent and fatal irruptions and plunderings of the above-named nations.

…

Then all the councilors, together with that proud tyrant Gurthrigern [Vortigern], the British king, were so blinded, that, as a protection to their country, they sealed its doom by inviting in among them like wolves into the sheep-fold), the fierce and impious Saxons, a race hateful both to God and men, to repel the invasions of the northern nations. Nothing was ever so pernicious to our country, nothing was ever so unlucky. What palpable darkness must have enveloped their minds-darkness desperate and cruel! Those very people whom, when absent, they dreaded more than death itself, were invited to reside, as one may say, under the selfsame roof.[48]

The “fierce and impious Saxons” practiced the old pagan belief in the Norse gods and had not received Christianity. The History of the Britons states of this time:

Vortigern then reigned in Britain. In his time, the natives had cause of dread, not only from the inroads of the Scots and Picts, but also from the Romans…

The Anglo-Saxons agreed to fight against the raiders to relieve the Britons from this trouble, and arrived in three ships with their leaders, Hengest and Horsa – princes descended from Woden, the Anglo-Saxon name for the Old Norse name Odin. Gildas writes of the arrival of the Anglo-Saxon mercenaries:

A multitude of whelps came forth from the lair of this barbaric lioness, in three cyuls, as they call them, that is, in their ships of war, with their sails wafted by the wind and with omens and prophecies favourable, for it was foretold by a certain soothsayer among them, that they should occupy the country to which they were sailing three hundred years, and half of that time, a hundred and fifty years, should plunder and despoil the same. They first landed on the eastern side of the island, by the invitation of the unlucky king, and there fixed their sharp talons, apparently to fight in favour of the island, but alas! more truly against it. [49]

Bede, in his 7th-8th century “Ecclesiastical History of the English People” writes from the Anglo-Saxon perspective of the arrival of his own ancestors, and places the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons in AD 449 at the start of the reign of Emperor Marcian. When the Anglo-Saxons arrived, Bede writes they:

[H]ad a place in which to settle assigned to them by the same king, in the eastern part of the island, on the pretext of fighting in defence of their country, whilst their real intentions were to conquer it.

Bede writes of the Germanic tribes who came to Britain:

Those who came over were of the three most powerful nations of Germany—Saxons, Angles, and Jutes. From the Jutes are descended the people, of Kent, and of the Isle of Wight, including those in the province of the West-Saxons who are to this day called Jutes, seated opposite to the Isle of Wight. From the Saxons, that is, the country which is now called Old Saxony, came the East-Saxons, the South-Saxons, and the West Saxons. From the Angles, that is, the country which is called Angulus, and which is said, from that time, to have remained desert to this day, between the provinces of the Jutes and the Saxons, are descended the East-Angles, the Midland-Angles, the Mercians, all the race of the Northumbrians, that is, of those nations that dwell on the north side of the river Humber, and the other nations of the Angles. The first commanders are said to have been the two brothers Hengist and Horsa… They were the sons of Victgilsus, whose father was Vitta, son of Vecta, son of Woden; from whose stock the royal race of many provinces trace their descent.[50]

The 8th century “Anglo-Saxon Chronicle” for the year 449 appears to quote Bede, but adds that the Anglo-Saxons first landed at a place called Ebbesfleet.

In their days the Angles were invited here by King Vortigern, and they came to Britain in three longships, landing at Ebbesfleet. King Vortigern gave them territory in the south-east of this land, on the condition that they fight the Picts. This they did, and had victory wherever they went.

Another manuscript of the “Anglo-Saxon Chronicle” calls this place Wippidsfleet. The “History of the Britons” provides some additional information, including that they were given the Isle of Thanet off the coast of Britain, in addition to supplies, in return for their service as mercenaries, and dates the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons to 447 AD:

In the meantime, three vessels, exiled from Germany, arrived in Britain. They were commanded by Horsa and Hengist, brothers, and sons of Wihtgils. Wihtgils was the son of Witta; Witta of Wecta; Wecta of Woden; Woden of Frithowald; Frithowald of Frithuwulf; Frithuwulf of Finn; Finn of Godwulf; Godwulf of Geat, who, as they say, was the son of a god, not of the omnipotent God and our Lord Jesus Christ … but the offspring of one of their idols, and whom, blinded by some demon, they worshipped according to the custom of the heathen. Vortigern received them as friends, and delivered up to them the island which is in their language called Thanet, and, by the Britons, Ruym. Gratianus Aequantius at that time reigned in Rome. The Saxons were received by Vortigern, four hundred and forty-seven years after the passion of Christ….[51]

Bede describes the conditions of this agreement:

The newcomers received of the Britons a place to inhabit among them, upon condition that they should wage war against their enemies for the peace and security of the country, whilst the Britons agreed to furnish them with pay.

According to the “History of the Britons,” their pay was in clothing and provisions. After arriving in Britain, the Anglo-Saxons, under the command of Hengest and Horsa, defeated the raiders and drove them back.

The Anglo-Saxon Conquest

The peaceful relations that initially existed between the Britons and the Anglo-Saxons quickly spiraled downward. The Anglo-Saxons requested additional provisions, but King Vortigern refused, saying they had multiplied and their numbers were too great to support, that their services were no longer required, and that they should return home. Hengest persuaded Vortigern to allow him to send for more warriors from the continent, and that he would continue to fight for the cause of the Britons, to which Vortigern agreed. Bede writes:

When the news of their success and of the fertility of the country, and the cowardice of the Britons, reached their own home, a more considerable fleet was quickly sent over, bringing a greater number of men, and these, being added to the former army, made up an invincible force.

In the “History of the Britons,” Hengist tells Vortigern:

We are, indeed, few in number; but, if you will give us leave, we will send to our country for an additional number of forces, with whom we will fight for you and your subjects.

Vortigern agreed to this proposal, and Hengist sent messangers back to the continent. Sixteen ships came with warriors and family members, including Hengest’s own daughter, Rowena. Hengest hosted a dinner, and when Vortigern was intoxicated, he was inflamed with lust for the beauty of Rowena and insisted that she must be his, and that he would give anything for her. Vortigern offered the kingdom of Ceint (Kent) to Hengest in return for his daughter, and Hengest agreed. Unfortunately, the kingdom of Ceint was not his to give, and the rightful king, Guoyrancgonus, was defrauded of his own kingdom by the wiles of Vortigern and was forced to relinquish it due to the unexpected occupation of it by numerous Anglo-Saxon warriors. Since the numbers of the Anglo-Saxons had greatly increased, Vortigern was unable to fulfill his obligation to them, so the Anglo-Saxons began threatening and committing aggressive acts against the Britons. The “History of the Britons” states:

[T]he Britons replied, “Your number is increased; your assistance is now unneccessary; you may, therefore, return home, for we can no longer support you;” and hereupon they began to devise means of breaking the peace between them.

Gildas writes of the threats of the Anglo-Saxons:

Yet they complain that their monthly supplies are not furnished in sufficient abundance, and they industriously aggravate each occasion of quarrel, saying that unless more liberality is shown them, they will break the treaty and plunder the whole island. In a short time, they follow up their threats with deeds. [52]

Bede adds that the Anglo-Saxons allied with their former enemies, the Picts:

In a short time, swarms of the aforesaid nations came over into the island, and the foreigners began to increase so much, that they became a source of terror to the natives themselves who had invited them. Then, having on a sudden entered into league with the Picts, whom they had by this time repelled by force of arms, they began to turn their weapons against their allies. At first, they obliged them to furnish a greater quantity of provisions; and, seeking an occasion of quarrel, protested, that unless more plentiful supplies were brought them, they would break the league, and ravage all the island; nor were they backward in putting their threats into execution.

Hengest persuaded Vortigern to allow him to send for more warriors to fight the Scots and Picts and to conquer their lands from them and claim them for their own, including his own son Octa and his son’s brother Ebusa. Vortigern agreed, and additional warriors arrived in the north in forty ships to launch an invasion of northern Britain. The “History of the Britons” states:

Hengist, after this, said to Vortigern, “I will be to you both a father and an adviser; despise not my counsels, and you shall have no reason to fear being conquered by any man or any nation whatever; for the people of my country are strong, warlike, and robust: if you approve, I will send for my son and his brother, both valiant men, who at my invitation will fight against the Scots, and you can give them the countries in the north, near the wall called Gual.” The incautious sovereign having assented to this, Octa and Ebusa arrived with forty ships. In these they sailed round the country of the Picts, laid waste the Orkneys, and took possession of many regions, even to the Pictish confines.

But Hengist continued, by degrees, sending for ships from his own country, so that some islands whence they came were left without inhabitants; and whilst his people were increasing in power and number, they came to the above-named province of Kent.

The 8th century “Anglo-Saxon Chronicle” writes of these reinforcements:

449 … They then sent to Angel, commanded more aid, and commanded that they should be told of the Britons’ worthlessness and the choice nature of their land. They soon sent hither a greater host to help the others…

According to the “History of the Britons,” Vortigern’s son Vortimer became deeply concerned by the growing aggression and spread of the Anglo-Saxons, and the aggressions led to battles:

At length Vortimer, the son of Vortigern, valiantly fought against Hengist, Horsa, and his people; drove them to the isle of Thanet, and thrice enclosed them within it, and occupied, hit, threathened and freightened them on the western side.

The Saxons now despatched deputies to Germany to solicit large reinforcements, and an additional number of ships with many men: and after he obtained these, they fought against the kings of our peoples and princes of Britain[39], and sometimes extended their boundaries by victory, and sometimes were conquered and driven back.

Four times did Vortimer valorously encounter the enemy[40]; the first has been mentioned, the second was upon the river Darent, the third at the Ford[41], in their language called Epsford, though in ours Set thirgabail[42], there Horsa fell, and Catigern, the son of Vortigern;

Of the latter battle, Bede writes:

Of these Horsa was afterwards slain in battle by the Britons, and a monument, bearing his name, is still in existence in the eastern parts of Kent. [53]

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle writes of this battle:

455 This year Hengist and Horsa fought Vortigern the king, in the place called Aegelesthrep, his brother Horsa was killed, and after that Hengist and Aesc received the kingdom.

Continuing the battles of Vortimer from the “History of the Britons”:

[T]he fourth battle he fought, was near the stone[43] on the shore of the Gallic sea, where the Saxons being defeated, fled to their ships[44].

After a short interval Vortimer died; before his decease, anxious for the future prosperity of his country[45], he charged his friends to inter his body at the entrance of the Saxon port, viz. upon the rock where the Saxons first landed; “for though,” said he, “they may inhabit other parts of Britain, yet if you follow my commands, they will never remain in this island.” They imprudently disobeyed this last injunction, and neglected to bury him where he had appointed.

From these descriptions, the battles of Vortimer were at the following locations in southeastern Britain:

-

- At the Isle of Thanet

-

- Upon the river Darent (A tributary of the Thames in Kent)

-

- At the ford of Epsford or Set Thirgabail (Battle of Aylesford) = Aegelesthrep

-

- On the shore of the Gallic sea

According to the “History of the Britons”:

And let him that reads understand, that the Saxons were victorious, and ruled Britain, not from their superior prowess, but on account of the great sins of the Britons: God so permitting it.

Hengest and his elders developed a plan to overthrow Vortigern – at a feast they would get Vortigern and his 300 nobles intoxicated and then massacre them, keeping Vortigern alive for ransom. The plan was effected, and Vortigern offered the provinces of Essex, Sussex, and Middlesex in (whether or not he had the right to offer those regions) to secure his own release.

Hengist, under pretence of ratifying the treaty, prepared an entertainment, to which he invited the king, the nobles, and military officers, in number about three hundred; speciously concealing his wicked intention, he ordered three hundred Saxons to conceal each a knife under his feet, and to mix with the Britons; “and when,” said he, “they are sufficiently inebriated, &c. cry out, ‘Nimed eure Saxes,’ then let each draw his knife, and kill his man; but spare the king, on account of his marriage with my daughter, for it is better that he should be ransomed than killed.”

The king with his company, appeared at the feast; and mixing with the Saxons, who, whilst they spoke peace with their tongues, cherished treachery in their hearts, each man was placed next his enemy. After they had eaten and drunk, and were much intoxicated, Hengist suddenly vociferated, “Nimed eure Saxes!” and instantly his adherents drew their knives, and rushing upon the Britons, each slew him that sat next to him, and there was slain three hundred of the nobles of Vortigern. The king being a captive, purchased his redemption, by delivering up the three provinces of East, South, and Middle Sex, besides other districts at the option of his betrayers.

The 8th century “Anglo-Saxon Chronicle” writes of Hengest and his people:

First of all, they killed and drove away the king’s enemies; then later they turned on the king and the British, destroying through fire and the sword’s edge.

Forever after, Vortigern was remembered as a traitor to the people of Britain.

The Lowlands of Scotland were inhabited by several kingdoms of Britons who formed a resistance against the invaders. When the Anglo-Saxons invaded Britain, they established kingdoms along the south and eastern coasts of Britain; the Britons who escaped fled to their kin in Southern Scotland, Wales, Cornwall, and Brittany in France where their descendants remain to this day. Thus, the descendants of the ancient Britons include the Welsh, the Cornish, the Bretons of France, some of the Lowland Scots, and the conquered Britons intermingled with the Anglo-Saxons to eventually become the English. Gildas writes of the destruction caused by the Anglo-Saxons. Bede writes:

For here, too, through the agency of the pitiless conqueror, yet by the disposal of the just Judge, it ravaged all the neighbouring cities and country, spread the conflagration from the eastern to the western sea, without any opposition, and overran the whole face of the doomed island. Public as well as private buildings were overturned; the priests were everywhere slain before the altars; no respect was shown for office, the prelates with the people were destroyed with fire and sword; nor were there any left to bury those who had been thus cruelly slaughtered. Some of the miserable remnant, being taken in the mountains, were butchered in heaps. Others, spent with hunger, came forth and submitted themselves to the enemy, to undergo for the sake of food perpetual servitude, if they were not killed upon the spot. Some, with sorrowful hearts, fled beyond the seas. Others, remaining in their own country, led a miserable life of terror and anxiety of mind among the mountains, woods and crags.[54]

Vortigern may be mentioned on the Pillar of Eliseg, erected in the 8th or 9th century monument in Denbighshire, Wales. The Latin text on this pillar was transcribed by Edward Llwyd in 1696 although the inscription is now mostly worn away. A translation of part of this text states:

Britu moreover son of Guarthigern, whom Germanus blessed and whom Severa, bore to him, the daughter of Maximus the King, who slew the king of the Romans.[55]

Robert Vermaat in his article “The Text of the Pillar of Eliseg,” notes that the Germanus mentioned here is the 5th century Germanus of Man, and not the 4th/5th century Germanus of Auxerre.

The Anglo-Saxons had secured a strong foothold in southeastern Britain, where they established the first Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Kent. Their kinsman – Angles, Saxons, and Jutes – continued to arrive from the continent to strengthen their efforts to subdue the island of Britain. In a desparate bid for survival, some of the British kingdoms banded together to oppose their quickly advancing foes.

The British Resistance

Gildas describes the conditions in some regions of Britain in the most desperate terms:

Some therefore, of the miserable remnant, being taken in the mountains, were murdered in great numbers; others, constrained by famine, came and yielded themselves to be slaves for ever to their foes, running the risk of being instantly slain, which truly was the greatest favour that could be offered them: some others passed beyond the seas with loud lamentations instead of the voice of exhortation.

“Thou hast given us as sheep to be slaughtered, and among the Gentiles hast thou dispersed us.”

Others, committing the safeguard of their lives, which were in continual jeopardy, to the mountains, precipices, thickly wooded forests, and to the rocks of the seas (albeit with trembling hearts), remained still in their country.

In these alarming circumstances, an armed resistance to the invaders rallied under the one hero who Gildas names – a Romano-Briton named Ambrosius Aurelianus.[56]

But in the meanwhile, an opportunity happening, when these most cruel robbers were returned home, the poor remnants of our nation (to whom flocked from divers places round about our miserable countrymen as fast as bees to their hives, for fear of an ensuing storm), being strengthened by God, calling upon him with all their hearts, as the poet says,—”With their unnumbered vows they burden heaven,” that they might not be brought to utter destruction, took arms under the conduct of Ambrosius Aurelianus, a modest man, who of all the Roman nation was then alone in the confusion of this troubled period by chance left alive. His parents, who for their merit were adorned with the purple, had been slain in these same broils, and now his progeny in these our days, although shamefully degenerated from the worthiness of their ancestors, provoke to battle their cruel conquerors, and by the goodness of our Lord obtain the victory.”[57]

Ambrosius Aurelianus is an intriguing figure. Although his parent’s names are unknown, the statement that his parents “for their merit were adorned with the purple” suggests they may have been granted that right by his father serving as a military tribune or a provincial governor of consular rank, and that he was therefore of high birth.

The Roman surname Aurelianus is of special interest. This suggests he came from the Roman plebeian gens (clan) Aurelia. The original surname would be Aurelius, but the –anus/-enus suffix suggests he was formally adopted into another gens, similar to how Gaius Octavius changed his name to Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus when adopted by Julius Caesar as noted by Dr. Tim Venning. This passage by Gildas also indicates several more things about Ambrosius: that his parents were killed by invaders – probably Anglo-Saxons; that he was a “modest man,” suggesting a sense of humility and that he was not seeking power and glory through conquest, but only sought to defend his people; and that he was a devout Christian along with those he led into battle. Gildas also indicates that the descendants[58] (probably grandchildren) of Ambrosius were his own contemporaries, and that they continued to “provoke to battle their cruel conquerors, and by the goodness of our Lord obtain the victory,” although they had “shamefully degenerated from the worthiness of their ancestors.”

The 7th–8th century Anglo-Saxon monk Bede mentions Ambrosius in his “Ecclesiastical History of the English People,” but his mention of him only paraphrases Gildas and does not provide any additional information about him.[59] A youth named Ambrose, or Ambrosius, appears in the “History of the Britons,” who seems to be the same Ambrosius Aurelianus mentioned in the writings of Gildas. In the “History of the Britons,” Vortigern seeks counsel from his twelve “wise men” since the Anglo-Saxons had seized control of several kingdoms of the Britons. They advise him to flee and built a fortress to defend himself.

Vortigern travelled “to a province called Guenet” in the mountains of Heremus, and there he found a summit that was well-adapted to a fortification. His “wise men” counseled him to build there. After attempting to collect building materials that kept disappearing at night, he asked his “wise men” what was causing this trouble. They told him that he “must find a child born without a father, put him to death, and sprinkle with his blood the ground on which the citadel is to be built, or you will never accomplish your purpose.”

In a region called Glevesing, Vortigern’s messengers found a boy that other children were mocking for not having a father. One boy says to the other, “O boy without a father, no good will ever happen to you.” Upon hearing this, the messengers inquire of the boy’s mother who claims, “’In what manner he was conceived I know not, for I have never had intercourse with any man,’ and then she solemnly affirmed that he had no mortal father.”